We all love a good anagram. The thrill of unscrambling "listen" to find "silent" is a small but satisfying mental victory. But what if I told you that the most complex, high-stakes anagram game in the universe is happening inside every cell of your body, right now? And what if I told you that losing this game could have deadly consequences?

This isn't science fiction. This is the bizarre and terrifying reality of DNA palindromes. Your genetic code, the very blueprint of your existence, is riddled with these strange, self-referential sequences. And according to cutting-edge molecular biology, these naturally occurring "anagrams" are one of the biggest threats to your genomic stability. They are fragile sites, prone to snapping, breaking, and causing the kind of genetic chaos that leads to cancer and other devastating diseases.

The Chromosome Killers Hiding in Your Genes

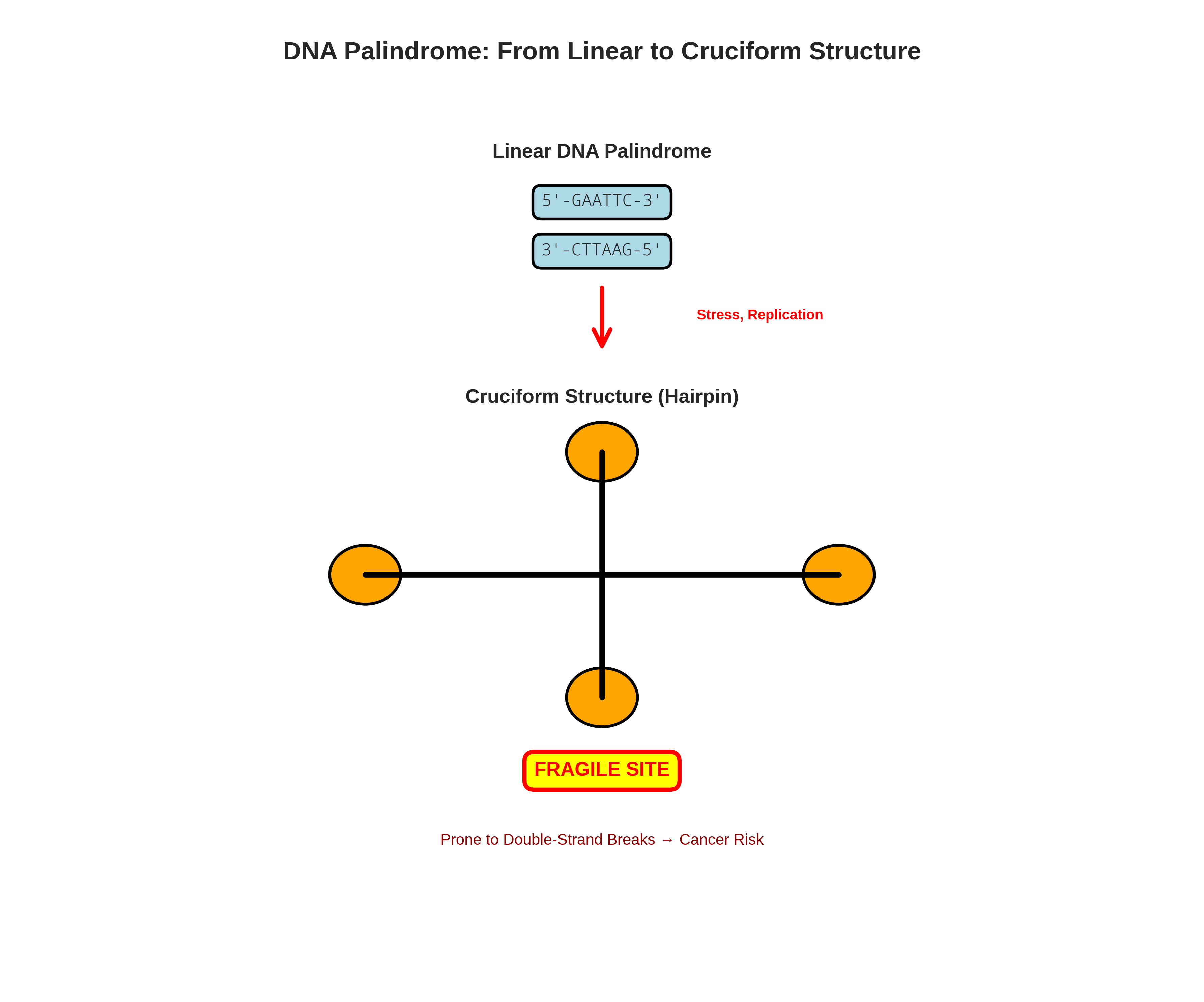

A DNA palindrome is a sequence of nucleic acid that is identical to its own reverse complement. Think of it like the word "RACECAR", but on a molecular scale. For example:

5'-GAATTC-3'

3'-CTTAAG-5'

Read the top strand left-to-right and the bottom strand right-to-left: identical sequences.

While some of these palindromes serve important biological functions, like acting as binding sites for proteins, many are essentially ticking time bombs embedded in our genetic code. Why? Because these sequences have a dangerous habit of rearranging themselves.

Under the right conditions—cellular stress, DNA replication errors, or transcription—a DNA palindrome can fold back on itself, forming a bizarre and unstable secondary structure called a cruciform or hairpin. Imagine a long zipper suddenly trying to zip up with itself in the middle. The result is a tangled, stressed-out mess.

"Palindromes are known as fragile sites in the genome, sites prone to chromosome breakage which can lead to various genetic rearrangements or even cell death."

This structural anomaly is a red flag for your cellular machinery. It can cause DNA replication to stall and, in the worst-case scenario, lead to a double-strand break (DSB)—the most lethal form of DNA damage. It's the molecular equivalent of snapping a chromosome in half.

The Anagrams of Cancer

When your cells try to repair these palindrome-induced breaks, things can go horribly wrong. The repair process is messy, and it often results in massive genetic rearrangements. This is where the connection to cancer becomes terrifyingly clear.

One of the hallmarks of many cancer cells is a phenomenon called palindromic amplification. This is where a gene, often an oncogene (a gene that can cause cancer), gets copied over and over again in a palindromic structure. This leads to a massive overproduction of the cancer-causing protein, driving the aggressive growth of tumors.

| Syndrome/Cancer Type | Palindrome-Mediated Mechanism | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | Palindromic amplification of HER2 gene | Aggressive tumor growth |

| Glioblastoma | Palindromic amplification of EGFR gene | Poor treatment prognosis |

| Male Infertility | Deletions on the Y chromosome | Azoospermia (no sperm) |

| Charcot-Marie-Tooth | Duplications on chromosome 17 | Neurological disorder |

| Leukemia | Translocations at palindromic sites | Uncontrolled cell division |

This isn't a rare occurrence. These palindromic rearrangements are found in a wide range of human cancers and genetic disorders. The very structure that makes anagrams a fun puzzle—the ability to be rearranged—is what makes DNA palindromes so dangerous.

What Can We Do About It?

Understanding DNA palindromes is crucial for advancing cancer research. Scientists are now working on:

- Mapping fragile sites: Identifying all palindromic sequences that pose cancer risks

- Targeted therapies: Developing drugs that stabilize palindromic regions

- Early detection: Using palindrome profiles to predict cancer susceptibility

- Gene editing: Exploring CRISPR techniques to modify dangerous palindromes

So the next time you use our anagram solver to unscramble some letters, take a moment to appreciate that the same principle of rearrangement governs life itself—for better and for worse.

While you can't control your DNA palindromes, you can sharpen your pattern recognition skills with word puzzles:

Frequently Asked Questions

A DNA palindrome is a sequence of nucleotides that reads the same forward on one strand as it does backward on the complementary strand. For example, 5'-GAATTC-3' paired with 3'-CTTAAG-5'. Unlike word palindromes like 'RACECAR', DNA palindromes involve complementary base pairing across both strands of the double helix.

DNA palindromes can fold into unstable cruciform (hairpin) structures during replication. These structures create 'fragile sites' prone to double-strand breaks - the most dangerous form of DNA damage. When cells try to repair these breaks, errors can lead to genetic rearrangements, gene amplification, and cancer-driving mutations.

No. Many DNA palindromes serve important biological functions, such as providing binding sites for proteins, acting as regulatory sequences, or functioning in DNA replication origins. The danger comes from longer palindromes with high sequence similarity and short spacers, which are more likely to form unstable secondary structures.

Palindromic amplification is a hallmark of cancer cells where genes (especially oncogenes) get copied repeatedly in a palindromic structure. This leads to massive overproduction of cancer-causing proteins, driving aggressive tumor growth. It's commonly seen in breast cancer (HER2) and brain tumors (EGFR).

Researchers are developing methods to identify and map palindromic sequences in genomes. Understanding these fragile sites may lead to targeted therapies that protect against palindrome-induced breaks or more accurately predict cancer risk based on an individual's palindrome profile.

References

- Miklenić, M. S., & Svetec, I. K. (2021). Palindromes in DNA—A Risk for Genome Stability and Implications in Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(6), 2840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22062840

- Tanaka, H., & Yao, M. C. (2009). Palindromic gene amplification—an evolutionarily conserved role for DNA inverted repeats in the genome. Nature Reviews Cancer, 9(3), 216-224.

- Lobachev, K. S., et al. (2007). Hairpin- and cruciform-mediated chromosome breakage: causes and consequences in eukaryotic cells. Frontiers in Bioscience, 12, 4208-4220.