When we think of the heroes of World War II, we picture soldiers on the beaches of Normandy and pilots in the skies over Britain. But some of the most important battles of the war were fought not with guns, but with pencil and paper, in the quiet, code-breaking huts of Bletchley Park. And the weapon that these brilliant minds wielded was, in its purest form, the anagram.

That's right. The entire field of transposition ciphers, a cornerstone of military cryptography for centuries, is nothing more than the art of creating and solving anagrams on a massive scale. The work of Alan Turing and his team in cracking the German Enigma code was, at its heart, the most high-stakes anagram puzzle in human history. And the principles they used are still fundamental to the work of intelligence agencies like the CIA and NSA today.

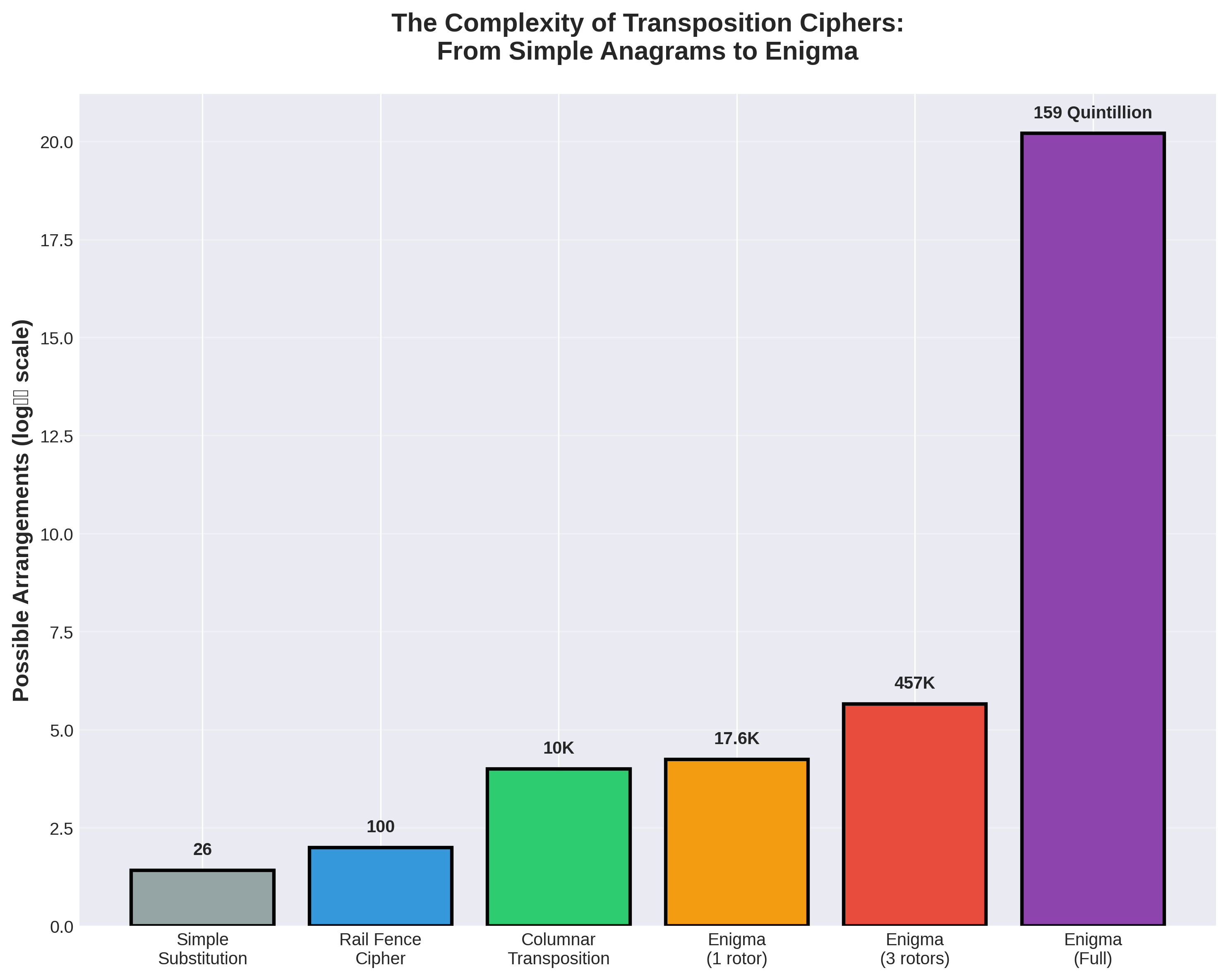

The Enigma: A 159-Quintillion-Letter Anagram

A transposition cipher doesn't change the letters in a message; it just rearranges them. It is, by definition, an anagram. A simple example is a rail fence cipher:

Message: WE ARE DISCOVERED FLEE AT ONCE

Rail fence pattern:

W . . . E . . . C . . . R . . . L . . . T . . . C . . E . R . D . S . O . E . E . F . E . A . O . N . E

Ciphertext: WECRLTEERDSOEEFEAONE

To the untrained eye, this is gibberish. But to a cryptanalyst, it's an anagram waiting to be solved. The letters are all there; only their order has been changed.

The German Enigma machine was a terrifyingly complex version of this. It was an electromechanical device that automated the process of transposition. With its series of rotating rotors and a plugboard, it could scramble a message into one of 159 quintillion possible arrangements. Every single day, the codebreakers at Bletchley Park were faced with a new, impossibly complex anagram puzzle.

"In transposition ciphers, the letters of the message are simply rearranged, effectively generating an anagram."— Simon Singh, The Black Chamber

Anagramming: The Codebreaker's Secret Weapon

How did they solve it? They used a technique that is literally called anagramming. In cryptanalysis, anagramming is the process of taking a piece of ciphertext and trying to rearrange the letters to form plausible words. It's a combination of frequency analysis (which letters appear most often?), pattern recognition, and sheer linguistic intuition—the same skills you use with our Jumble Solver or Crossword Solver.

Alan Turing's great breakthrough was to automate this process. He designed a machine called the Bombe, which could test thousands of possible Enigma settings per second. The Bombe wasn't just a brute-force machine; it was a logic machine. It looked for contradictions in the ciphertext, ruling out impossible arrangements until it found the one that produced coherent German words.

In essence, Turing built the world's first high-speed, automated anagram solver. And it changed the course of the war. The intelligence gained from cracking the Enigma code, known as "Ultra," is estimated to have shortened the war by at least two years, saving millions of lives.

| Cryptographic Term | Anagram Equivalent |

|---|---|

| Transposition Cipher | Anagram |

| Ciphertext | Jumbled Letters |

| Plaintext | Solved Anagram |

| Anagramming (technique) | Solving the Anagram |

| The Bombe | AnagramSolver.com |

Modern Spies and Their Word Games

You might think that in the age of supercomputers and quantum cryptography, the humble anagram would be obsolete. You would be wrong. The fundamental principles of transposition are still a key part of modern encryption. While today's ciphers are far more complex, they still rely on the core ideas of permutation and substitution—shuffling and replacing.

Intelligence agencies like the NSA and CIA still employ armies of linguists and mathematicians whose job is to find patterns in seemingly random data. They are looking for the statistical fingerprints that all languages leave behind, no matter how well they are scrambled. They are, in a very real sense, still solving anagrams.

Declassified NSA documents reveal that techniques like frequency analysis and contact charts (which letters are likely to appear next to each other) are still fundamental to cryptanalysis. These are the exact same techniques that a casual puzzle enthusiast uses to solve a Wordle or unscramble a Scrabble rack.

Try It Yourself: Think Like a Codebreaker

Want to experience the thrill of cryptanalysis? Our Anagram Solver uses the same principles that Turing's Bombe used—pattern matching, frequency analysis, and dictionary lookups—to crack any jumbled word in milliseconds.

The Stakes Were Real

So the next time you're struggling with an anagram, remember the stakes. You are engaging in a mental exercise that has toppled empires, won wars, and remains a crucial tool in the shadowy world of international espionage. The same cognitive skills that help you solve a Spelling Bee puzzle or find Words With Friends moves are the same skills that broke the Enigma code.

It's not just a game; it's a matter of national security.

References

- Singh, S. (n.d.). The Black Chamber: Transposition. simonsingh.net

- Imperial War Museums. (n.d.). How Alan Turing Cracked The Enigma Code. iwm.org.uk

- National Security Agency. (1988). Fifty Years of Mathematical Cryptanalysis (1937-1987). Declassified document available at governmentattic.org.